Murder on the Paris Métro: the unsolved death and mysterious life of Laetitia Toureaux

It was a warm May evening in Paris, 1937. Porte Dorée métro station was busier than normal for a Sunday because the next day was a public holiday and many were making the most of it by heading out for a night on the town. Among the passengers waiting on the platform was a family group of three on their way to the theatre. They had positioned themselves in the middle of the platform where the train’s first-class carriage – the third of its five carriages – would arrive. A few metres to their left were three women, also intent on boarding first class.

At 6:28 pm the train pulled into the station. As Major Dubreuil, a 27-year old military dentist and one of the family group, would later recall, no one exited the carriage as they got on. There could be no mistake on this point because his group entered through one door and the women entered through the second. There was one person already in the carriage: a young woman in a green suit sitting on a bench on the nearside as they entered, her back to them. Just as they began to move forward to take their seats, the woman slumped forward and fell onto the floor. Dubreuil, who had medical training, approached her to assist. It was then that he saw a knife protruding from her neck, embedded so deeply that only the handle was visible. He examined the injured woman, who was still alive and trying to speak, but saw that her jugular vein had been severed and surmised that she would not survive. In seemingly inexplicable move, Dubreuil and his group immediately got off the train and left the station.

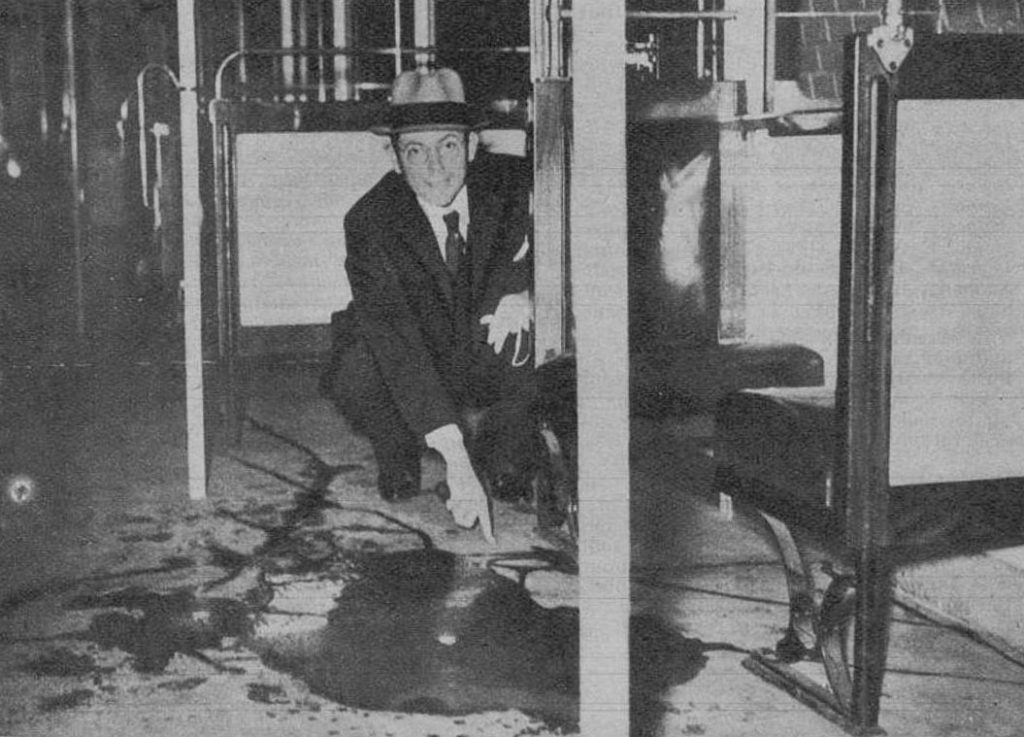

The women who remained in the carriage began to scream, alerting the train’s conductor that something was seriously amiss, as well as drawing the attention of the passengers in other parts of the train. Arriving on the scene, the conductor had the women get out the carriage, and was able to prevent others from entering, though not from seeing the fallen women and the smears of blood that surrounded her, descriptions of which would be repeated in press coverage of the crime in the days and weeks to come.

While the conductor attempted to control the situation underground, another Métro employee was able to hail down a policeman, Agent Isambert, in the street for help. Isambert raced down to the quayside where, seeing that the victim was conscious and trying to speak, he grabbed the knife handle and pulled the dagger free from her neck, thinking that it would make it easier for her to speak. The knife, though, had been acting as a kind of stopper its removal caused blood to gush from the wound. The woman immediately lost consciousness, bleeding out on the floor.

As she lay dying, more police came, led by Chief Inspector André Baillett. They found the woman’s handbag and were able to identify her as Laetitia Toureaux, a 29-year-old Italian and resident of the nearby 20th arrondissement. An ambulance arrived. Laetitia was placed on a stretcher and removed from the station but she would not survive the trip to the hospital.

Murder on the Métro

Even if none of what emerged afterwards had come to pass, Laetitia Toureaux would still have the curious distinction of being a macabre footnote in Paris history: she was the first person to be murdered on the Paris Métro. This was somewhat surprising given that the underground rail network had been been open for 37 years and – in all likelihood – there would have been other murders before, but not of attractive women in first class. So it was that Laetitia was the Métro’s first official victim, and the story was an immediate press sensation.

The details of the killing were shocking. How could a vibrant young woman be brutally slain on a busy train? Was there a homocidal maniac on the loose? Was a vengeful lover responsible? How safe were Parisian women on the city’s transport system?

Details of Laetitia’s life were made public and raked over by journalists, the public – not to mention the police. The immediate facts were that she was a widow, living alone, her husband having died three years earlier from tuberculosis. She worked in a factory in Saint Ouen, a suburb to the north of Paris, that made shoe wax. Laetitia was close with her mother, sister and two brothers, all of whom lived nearby in an area of Paris popular with Italian emigrées. The family were originally from the Valle d’Aosta region of Italy but had emigrated to France when Laetitia had been a teenager. Since her husband’s death, Laetitia had had a few casual romantic relationships but nothing had lasted; her grief had been real and lasting. In a sad detail, it emerged that the day she died had been the first time she hadn’t worn the black clothes of mourning, instead she had been wearing a new green suit, made for her by her mother.

No one had a bad word to say about Laetitia. She was a popular young woman who worked hard, lived quietly, and was close to her family. The one detail that could be said to stand out was that in her free time she enjoyed attending des bals musettes – musical balls – but so did thousands of young Parisians. It seemed baffling that anyone would want Laetitia dead.

But this was just one part of the puzzle surrounding the murder on the Métro. The other was not who did it, but how. Police investigators, from the very start, found themselves grappling with a set of circumstances in which it was seemingly impossible for a murder to have taken place – and yet it had. Laetitia had boarded the train alone at one station, then was found dying 90 seconds later at the next. In that time, no one had got into or out of her carriage. So how had she been killed?

The locked room mystery

It was like a mystery from detective fiction was playing out in real life. Without Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot to help unveil the cunning trick, police were forced to comb through the details of Laetita’s movements to see if any clue could be found there.

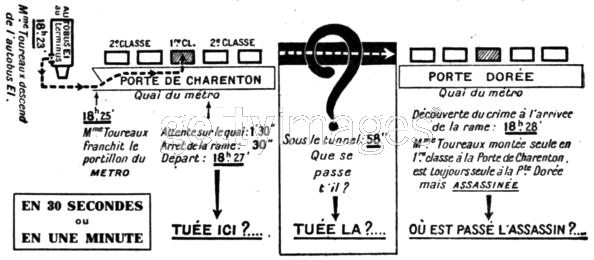

Earlier in the day, Laetitia Toureaux had eaten lunch with her mother and other family members. She then spent the afternoon dancing with her younger brother and friends at L’Ermitage, a dance hall, in Maisons-Alfort. At 6 pm she said her farewells and took the bus alone to the Porte de Charenton Métro station, arriving at 6.24 pm. Still alone – and, according to witnesses, not followed – she bought a ticket and descended the steps to the platform. Porte de Charenton was the first station on the line. Laetitia didn’t have long to wait – her train pulled into the station at 6.25. Among the dozens of passengers, Laetitia was the only person to board the first class carriage. She took a seat on a bench seat and sat facing the interior of the carriage, her back to the door. None of the witnesses on the platform that evening saw anyone enter the carriage with Laetitia, nor did anyone get on before the train departed at 6.27 pm.

The train’s journey from Porte de Charenton to the next station, Porte Dorée, took 90 seconds. Witnesses in the second-class carriage on either side Laetitia’s swore that, during the short trip, no one entered or exited from either of the adjoining doors. Police were later able to confirm that the doors were locked and hadn’t been tampered with. Finally, the six people who got into Laetitia’s carriage and found the injured woman, also swore that no one had got off.

According to witnesss statements, Laetitia Toureaux had been alone when she entered the empty carriage, alone when the train departed, that no one had entered while the train was in motion, and no one had left upon its arrival. And yet somehow she had been killed and her killer had vanished.

Evidence

The most tangible piece of evidence available to the police was Laetitia’s body. The autopsy showed that Laetitia had been killed with a single stab wound, just behind her right ear, and that the blow had been delivered with great force and precision. A lot could be deduced from the nature of the killing. Firstly, it ruled out a female assassin because very few women have the upper body strength to carry out this type of stabbing. Secondly, it put paid to any notion that Laetitia may have died by suicide – a tempting theory which fit the circumstances of her death, but not the manner. Finally, the single blow revealed a lot about the personality of the killer. It was an efficient act, not the frenzied attack of a random maniac. Add to this the fact that Laetitia had not been robbed or sexually assaulted, and this crime looked all the more deliberate. Laetitia hadn’t been killed because she was in the wrong place at the wrong time: she had been targeted.

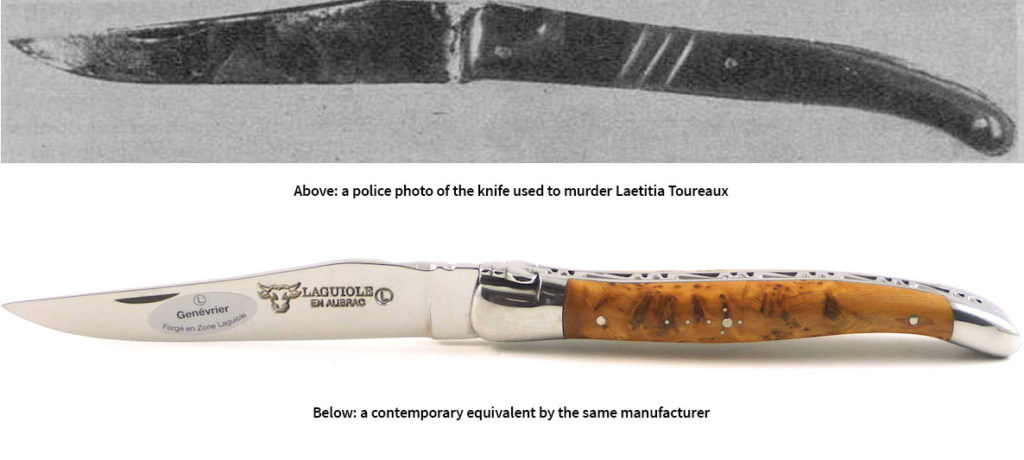

Then there was the knife. It was a 20 cm Laguiole model with a 9 cm blade and a bone handle. It was striking that the killer chose to leave the weapon embedded in his victim rather than dispose of it and risk it being traced back to him. As it was, attempts to find where it had been purchased came to nothing because it was a popular brand and was widely available. The police drew a further blank in their search for fingerprints. None were found on the knife and, while a great many were found on the handles and seatbacks where Laetitia had been sitting, none matched the fingerprints stored in police records. The most likely scenario was that the killer had been wearing gloves, which – on an unseasonably hot evening in May – gave further credence to the theory that this was a premeditated crime.

While the killer seemed ghostlike in in being able to vanish from the scene of the crime, this very ability told the police a great deal about the kind of person they were dealing with. Choosing to murder Laetitia in a public place and in an incredibly tight timeframe was an audacious act. In any scenario we can imagine for where or how the killing took place, there is always the possibility that a member of the public could appear and interrupt. That they didn’t was pure luck – but that the killer proceded in spite of the risks spoke volumes about the confidence of the man. Everything the police had learned so far was pointing their investigation in one direction: that Laetitia Toureaux had been killed by a professional hitman.

This, of course, seemed hugely improbable. Women are typically killed by current or former partners, or someone known to them; then there are the far less frequent attacks by homicidal and/or sexually motivated strangers. A professional hit on a young female factory worker was so unusual as to seem absurd – and yet all the hallmarks of the killing pointed to just that. As the police were to find out, nothing about Laetitia Toureaux’s life was quite as simple as it seemed on the surface.

But before we get there, we’re going to look more closely at how the killing is likely to have taken place. If we start from the basis that this was likely to be a professional hit, then three scenarios present themselves for what took place that day.

Theory 1: Laetitia was followed by her killer

To remind ourselves, prior to catching the Métro Laetitia had been dancing that afternoon with her brother and friends at a L’Ermitage dance hall. It is conceivable that someone observed her there, and followed her onto the bus, then into the station and down to the platform. When Laetitia entered the first-class carriage, she was alone for the first time in hours. For the killer, this was the only opportunity to commit the crime without being directly observed. We can imagine a scenario where Laetitia sits down, her back to the door, the killer enters, plunges the knife in and leaves immediately afterwards. The killer could either have fled the station, or – more brazenly – got onto a second-class carriage and mingled with the other passengers. (There’s also the additional possibility that he stayed in the carriage and exited at Porte Dorée – this is something we’ll pick up later.)

The trouble with this theory is that no one reported seeing anyone follow Laetitia, which is particularly problematic for the bus part of her journey. Had she travelled only on foot, it would be difficult to conclude that she hadn’t been trailed, but the bus driver said that Laetitia entered and exited the bus alone. While this doesn’t discount the possibility that she was followed, it certainly complicates things.

Theory 2: Laetitia’s killer was lying in wait

Let’s, for the moment, accept that the bus driver and other witnesses were correct in saying that Laetitia wasn’t being followed. We can imagine the same manner of killing and escape as above but – instead – the killer is already at Porte Charenton train station, or even inside the train carriage as she enters. One argument in favour of this is that first-class carriages were considerably more expensive than second class and thus were far less frequented, giving greater guarantees that they would be alone. Even so, anyone could have entered the carriage before or during the crime. Would an assassin choose to commit a crime there? Surely it’s more likely that the location was down to opportunity, not planning.

A further drawback to this theory is that it would require the killer to have detailed knowledge about Laetitia’s movement that day and her plans for that evening. How did he know that she was taking this particular train? Did he plot her movement beforehand and correctly guess that from point A to point B, the likeliest route would be by bus then métro? Complicating matters still is the intruiging fact that Laetitia was in the first-class carriage at all; normally she used second class to travel to work, yet in her handbag was a book of first-class tickets. (This latter fact enflamed the Paris press because it was known that first-class carriages were used by prostitutes to pick up clients, and questions about Laetitia presence there came into question.)

These concerns about a foreknowledge of Laetitia’s movements can be put to one side when we look at the final theory.

Theory 3: Laetitia had a pre-arranged meeting with her killer

Could Laetitia have had a rendez-vous with the man who was to kill her? Before leaving the dance, she told her friend Pierrette that she was late for an appointment. (According to another friend who attended the dance, Laetitia implied that she anticipated her evening to be unpleasant.) A meeting would explain why no one observed her being followed, and would mean that the killer knew exactly where she would be and when.

It is plausible, also, that the first-class carriage was chosen as a meeting place, given its relative privacy and that fact that it was a Sunday evening when there were fewer passengers around. Rather than being an unusual choice as a place to commit a murder, the killer may have bet that Laetitia would feel safer meeting him there than anywhere more secluded. A calculated risk that paid off.

And Laetitia was likely to have had real concerns for her safety. Just three days before her death, Laetitia was attacked after leaving the Métro station and – according to some accounts – the man was carrying a knife. Fortunately, on this occasion, she was able to fight off her attacker and escape to safety. While she did not report the incident to the police, and made light of it to friends, it is perhaps telling that on the morning of her death, she changed her hair colour and was wearing new clothes. Was Laetitia attempting to change her appearance? Did Laetitia know she was being targetted – and did she know who was behind it?

Part 2: The double life of Laetitia Toureaux

Sources

My main source for this article is this excellent book Murder in the Métro: Laetitia Toureaux and the Cagoule in 1930s France by Gayle K. Brunelle, Annette Finley-Croswhite (LSU Press) which helped fill in lots of blanks and straightened out some of the conflicting information I’d come across. I’ve also read a great many contemporary newspaper accounts via RetroNews.fr, the excellent French-language newspaper catalogue run by the French National Library. Finally, a big mention should go to the site Crimocorpus.org, a Museum of Crime, Justice and Punishment, via which I was able to access Detective (various issues), a French-language magazine that covered the story in great depth.

Pingback: The double life of Laetitia Toureaux – BEST FRANCE FOREVER